The Long Way from Non-Reductionism to Transdisciplinarity: Critical Questions about Levels of Reality and the Constitution of Human Beings

1.- Reductionism: from science to culture and every day life

“The vision of Nature in any given era depends on the imagination prevailing in that era which, in turn, depends on a multitude of parameters… Once formed, the image of Nature acts on all fields of knowledge”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

Why are we concerned about reductionism? We, in this case, means social scientists hoping to contribute with knowledge to social change brought about by public and private actors. Thus, from a social science perspective, besides a purely theoretical motivation, we are concerned with reductionism because it implies particular ideas in our everyday approach to reality, including our own human reality as a key presupposition that orients our action towards nature, our fellow human beings, and to what we can broadly call “transcendental or spiritual reality.”

How does a very scientific and abstract problem such as reductionism relate to culture and everyday life? If we agree that scientific knowledge precedes common sense, the problem of reductionism should arise in culture and everyday life as it has in science and philosophy. Throughout history, there has been a legitimate source of knowledge in every society. In our Western Middle Ages, this legitimate source was revelation, and therefore religion and its institutionalization: the Church. With the advent of Modernity, this legitimate source of knowledge changed to science. In modern Western societies, what science discovers and states as truthful becomes what common knowledge accepts and adopts. Of course, this is not linear, and there are other sources of knowledge which sometimes oppose science, or in a more constructive way, attempt to dialog with it.

Thus, if we are blaming reductionism for not being an accurate way of bringing about knowledge in science, we should expect problems in our daily life to come precisely from reductionistic ideas of understanding and relating to our natural and human world. This, unfortunately, has not received sufficient attention from social sciences on the one hand, and, on the other, the hard sciences are less concerned with the repercussions of their findings on society. This leaves us a field of inquiry open to research and reflections, and this will be our starting point for proposing our views.

The social sciences have looked at the problems confronting contemporary societies from different perspectives. Problems have been viewed as consequences of the globalization process (Beck,1998), as unexpected consequences of Modernity (Giddens,1995), as the colonization of the “lifeworld” by differentiated systems (Habermas,1992), or as consequences of functional differentiation of communicational systems (Luhmann,2007). But the complexity of our contemporary society is such that none of these approaches has gained consensus among either researchers or professionals. This fact invites us to continue developing new approaches and programs to observe social complexity and to provide other points of view that can help explain contemporary social phenomena.

2.- Reductionism in culture

“Paradoxically, everything is ready for our self-destruction, but at the same time, everything is also in place for a positive mutation, comparable to the great shifts in History”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

In this context, I have developed a socio-cultural perspective that draws from the theory of society offered by Niklas Luhmann, a contemporary German sociologist. He has constructed his social theory considering society as emerging autonomous levels of communications that organize themselves into functional systems. Society does not consist of an aggregate of human beings, but rather of communications. This leaves us humans as psychic systems in the environment of society, who relate to society through communications. My perspective identifies those communications (semantics) that remain presupposed in social communication and which have a direct, although not easily identified, relation to social problems that affect people in contemporary society.

It seems to me that at least some of our problems in modern society can be observed as extreme developments of the evolution of social communications that maintain these presupposed modern semantics. Also, to existing strategies for bringing about social change, we could add a specific socio-cultural intervention strategy based on the proposed observation.

My reading of Modernity is that of an epoch, a historical period characterized by a particular culture and by an institutionalization in accordance with that way of interpreting reality, society and the meaning of human life. As Jorge Larraín, a Chilean sociologist has stated, “All modernization is an interpretative field… a struggle to institutionalize the imaginary significations of Modernity in a particular way” (Larraín 2005:26). This perspective gives priority to the idea over the structural institutionalization that results from the intent to give concretion to the idea. Of course, this is one of the two possible ways of ending the circle of the recursive process that goes from the idea, the semantics, to the structure and from this to a new idea. Luhmann skips the problem of giving priority to one or the other part by using the hen and egg metaphor (which one is first), but his analyses start always from the structure. For me, on the contrary, the starting point and the focus of my interest is the semantics and, therefore, culture becomes important.

Thus, I propose a particular program to observe Modernity from a perspective that focuses on certain modern semantics that have undergone sedimentation and turned into presuppositions about the basic dimensions of social life: a general and abstract preconception of what it is to be a human being, a preconception of nature, of the meaning of life, of truth and transcendence.

Such presuppositions can be heuristically treated and organized into what I have called a socio-cultural matrix. My hypothesis is that such sedimented semantics that underlie our modern culture influence social communications by remaining tacit but included as presuppositions. Inasmuch as these presuppositions are always a reduction of the possibilities of interpreting human and social complexity, their persistence over time ends up producing problems that at the individual level are not recognized as effects of these presuppositions, and so their influencing power over social communications remains unchanged.

In relating modern semantics with problems that arise at the level of individuals in everyday life, I am posing a hypothesis that expresses itself at two levels. The more general one supposes that the predominant semantics in any given society throughout history favors unilaterally, or reductionistically, one or another interpretation of the complexity of the world and therefore end up, over time, bringing about individual and social discomfort which, in turn, gives rise to social change.

The second level of the hypothesis applies particularly to the modern age, and it supposes that a non-correspondence between modern semantics, for instance about individuality, and the complexity that human development has reached in this period could be an important source of problems that affect our present society.

If society is not conscious of the operating power of the socio-cultural matrix of sedimented semantics, it not only restricts its liberty to confront critically its present, but it may end up in reifications of certain social phenomena. Capitalism, colonialism or Eurocentrism will have a different weight as explicative causes if they are treated as historic-economic phenomena detached from the modern socio-cultural matrix than if they are observed as logical developments of a –temporary- way of understanding the world.

On the other hand, the contemporary social crisis, the polycrisis in Morin’s words, is not perceived as an “erratic phenomena…full of uncertainties and insecurities… completely out of control” as Wallerstein (1996) asserts. On the contrary, the perspective that takes into account the socio-cultural matrix recognizes in the crisis the incapacity of the old interpretations of the sedimented semantics to deal with the new complex phenomena that have developed in society. This perspective views the crisis as part of a larger process and is thus theoretically prepared to offer a better diagnosis of our critical present. For us, the crisis is the visible face of a historical moment that expresses the limits and problems of the modern presuppositions and, thus, it allows us to go beyond perplexity upon the crisis to identifying new semantics that will eventually replace those in crisis.

3.- A systemic concept of culture: the semantic domain and the socio-cultural matrix

“…often unconsciously, a certain logic and even a certain worldview hide behind each action, whatever it may be – the action of an individual, of a collectivity, of a nation, of a State”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

As far as I believe that the functionally differentiated systems of Luhmann’s social theory are not sufficient to address the symbolic context in which the lives of concrete individuals moves, I have used the concept of culture to observe the level of semantic contents that participate in social communications.

Integrated into the theoretical context of social systems theory, I propose a concept that views culture as an order emerging from communication. It consists of semantics that achieve different levels of sedimentation in relation to the expression of everyday language. These semantics play a role in reducing complexity by orienting social communications, making some of them more likely to be selected than others (Dockendorff, 2006). It is precisely this role of the implicit over society, particularly over the level of the daily living of concrete individuals, that justifies giving the sedimented semantics a theoretical importance, in addition to its relevance in designing initiatives for social change (Dockendorff, 2007).

I have expressed this concept of culture in a model that establishes a semantic domain and, as a specific part of this domain, a socio-cultural matrix. The semantic domain is the result of a gradual, graduated sedimentation process of semantics that ranges from the selections that are still used explicitly in communication to those that have reached a maximum degree of sedimentation and, while the latter do not appear in communication, there is coherence in meaning between the two.

Within the semantic domain model, we want to highlight particularly the segment that contains those semantics that are very general and of maximum sedimentation. In the maximum sedimentation extreme, we can distinguish a constellation of semantics that are sedimented to a maximum degree, which function as assumptions or presuppositions with respect to the basic categories of the entire observed world. This constellation of distinction schemes is deeply sedimented and their content is not, therefore, required by those participating in social communication. However, to the extent that they sensitize society toward certain contents of communication rather than others, they influence society through the coherence in meaning that they maintain with the selections used in social communication. Obviously, this coherence is not normative, so that new semantics can modify what has sedimented. We call this constellation of structuring semantics, which constitute a limited number of assumptions whose content reaches maximum degrees of topical generality about the world, the socio-cultural matrix.

The structuring function of the prevailing socio-cultural matrix implies that social communications will develop through logical steps as they reach objectives or arrive at stages that become points of departure for new communications which, while no other communications that might set them aside become sedimented, will continue under the same matrix that directs them. Thus, the implicit semantics, regardless of how general and abstract their content may be, are present in each new instance of social communication and, in the case of the modern socio-cultural matrix, which has prevailed for approximately 400 years, its developments have reached such extreme levels that they are recognized today as critical.

From this perspective, the socio-cultural matrix is that set of presuppositions on reality and the human being that underlie and guide the activities of all spheres of a society for a period of time. A socio-cultural matrix prevails for several centuries while human activity takes place under this way of viewing the world until there is an accumulation of ideas, perspectives, events, processes, and social movements that question this way of living and lead the socio-cultural matrix into a crisis. We hold that the flow of social communication, a process that is the foundation on which society evolves (Luhmann, 1991, 2007), is always based on what we call a socio-cultural matrix, which, as a result of the evolution itself of society, will eventually be replaced by a new one.

4.- Overcoming the reductionist Subject in philosophy and the social sciences: the crisis of modern epistemology

“…the ‘death of man’ is a phase of History that is, after all, necessary; it portends his rebirth”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

A key element through the evolution of Modernity, and about which there is a general consensus, is the presupposition of the rational identity of human beings, considering them “subjects.” After nearly 400 years of this prevailing assumption, today it is affirmed that, just as this modern subject emerged historically, it can also eventually die (Hall, Held and McGrew, 1992).

The questioning of the conception of subject converges with what in philosophy has been called the crisis of epistemology in modern philosophy. The episteme that has come to be discussed as being in crisis is the philosophical concept of the foundations of knowledge, based on the idea of a transcendental subject whose rationality, using logic, enables him to reach certainties and thus to distinguish between truth and falsehood.

The crisis of the modern episteme implies a veritable revolution within contemporary philosophy. Rorty (1995) presents himself as the spokesperson for this revolution, which he considers paradigmatic, in the Kuhnian sense, within philosophy. He identifies the true heroes of this revolution as Wittgenstein, Heidegger and Dewey, who rule out the notion of a foundation of knowledge and dispense with the idea, shared by Descartes and Kant, of the mind as endowed with the elements and processes that make knowledge possible. Without proposing alternate theories of knowledge or philosophies of the mind, revolutionary authors are inclined simply to leave epistemology and metaphysics aside, just as the 17th century philosophers turned away from scholasticism.

Following the development of modern epistemology, according to Foucault (1993), the modern age began when human beings started existing inside their heads. The idea of man being at the same time both empirical and transcendental has conducted philosophical thinking from Kant to the present. According to Rorty, after Descartes invented the mind, Kant invented the conditions for the possibility of scientific knowledge. They had imposed on themselves the task of finding a place in human consciousness where the activity of knowing took place. This could answer the question that arose after the war between science and theology was won by science: How is knowledge possible? This question could only arise after religion no longer prevailed over science, and it started the special philosophical concern called epistemology.

Following Rorty (1995), we can see that the Kantian assumption of the transcendental subject is located in the invisible place of subjectivity and that, in the act of learning, it distinguishes itself from that which it experiences. The invisible place of subjectivity implies that this subject is decontextualized; that is, not situated socially, culturally, or historically. Rorty (1995) has held that the Kantian assumption of the transcendental subject in the invisible place of subjectivity has become untenable. Hence, the idea of subject as the predominant semantics on the human being has been considered to be in crisis in communications of both the philosophical and social sciences. The notion of subject had become the semantic equivalent of the human being; it had turned into a reductionist concept of the human being, reduced to just some of his faculties, cut off from his social relations, and only poorly integrating his non-mental faculties.

Hall, Held and McGrew (1992) have followed the conception of subject through its evolution. They suggest an evolution from the enlightened subject as immutable substance to a sociological subject that is constructed socially, arriving at the post-modern subject that shows itself to be divided and fragmented. Authors speak of the birth and death of the modern subject. They hold that rational identity has been presupposed in modern thought, but, just as the modern subject emerged historically and has changed, so can it come to be replaced by some other conception of being human. They recognize five conceptual ruptures of the idea of subject, brought about by Marxist thought and that of Freud, Saussure, Foucault, and feminism. They affirm that these ideas have brought down both the Cartesian and sociological subject in late Modernity.

Foucault (1993) offers a criticism of the concept of Man, understood as subject, from a historical perspective. He holds that before the end of the 18th century, Man did not exist. Before that, Man was a topic of discussion for the natural sciences as a species and kind, but, adds Foucault, there was no epistemological awareness of man as such (op. cit.: 300). Man did not have a place in the episteme, either as subject or as object. “We are so blinded by the recent evidence of man,” Foucault tells us, “that we no longer have even the memory of the time, though not so long ago, when the world, its order, and human beings existed, but not Man” (op. cit.: 313). Reminding us that the modern idea of Man is historic and contingent, Foucault invites us to wonder if this Man still exists, or if he will necessarily continue to exist as a sedimented semantic presupposition in contemporary social communications.

For his part, Wittgenstein (1998, 2004) has criticized the Cartesian epistemological positions because they view the human being as a mere spectator of the world. Wittgenstein’s contribution to the crisis in traditional epistemology is crucial. His greatest conceptual contribution is that of the language game, a concept very near that of culture that we suggested earlier, and certainly near the idea of language as an action woven into culture. From Wittgenstein, language and culture constitute a world, which is always a world interpreted collectively in a certain way. In this perspective, there is no room for the Kantian subject closed off in the isolated place of subjectivity and not situated socially, culturally, or historically.

Wittgenstein, from the start of his Philosophical Investigations, shows how, through language games, people learn from childhood not only a language, but a form of social activity, a way of life. Language games, belonging to a specific linguistic community, are fundamentally social. Wittgenstein’s ideas that one can only “know” from within a language game seem to us to be similar to those of Luhmann (1991) and even Maturana (1990), except that instead of a language game, they speak of communications systems or of “worlds brought in by the hand.”

Thus it is that the evolution of the semantics of individuality, dealt with by several authors, has been particularly viewed as a crisis of the semantics of the subject, arising from what has been called the crisis of modern epistemology.

In sociology, Habermas and Luhmann have both made significant attempts to overcome Kantian epistemology because, in their respective views, it had affected critical theory (the former) and sociological tradition in general (the latter).

Habermas (1992) attempts to endow sociology, and critical theory in particular, with a new epistemological foundation. He proposes substituting the paradigm of consciousness dominated by the subject-object relationship with one of linguistic and hermeneutic origin in accord with the perspectives of Wittgenstein and Gadamer. According to Habermas, the consciousness paradigm does not include the relationships that subjects establish with each other, that is, the intersubjective dimension of knowledge in which the subjects recognize themselves as equals, generating a shared consciousness of the world. For his part, Luhmann (1991) diagnoses sociology as affected by epistemological obstacles which his systemic paradigm would overcome. His theory of second-order observation arises as a critical alternative to the Kantian subject. The image of the circular, recursiveness in systems theory (Luhmann,1991), is complemented with the ideas of complexity and emergence, which surface as alternatives to the idea of primary fundament.

In sum, philosophical literature leaves no doubt as to the crisis which the modern episteme has reached, a crisis that becomes more evident as the Kantian subject, an observer of the world, disconnected from his historical-social context, with the privileged capacity to access the truth, has become the equivalent of the human being. The result is a simplified human being, diminished not only from being cut off from his social relationships, but also from not integrating his non-mental dimensions. And that human being has reached a crisis point in human sciences and, progressively, in common sense.

5.- Overcoming the reductionistic notion of Subject: What is proposed in its stead?

“A mysterious factor of interaction, not reducible to the properties of the different individuals, is always present in human collectivities, but we always discard it into the hell of subjectivity”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

Where do these proposals for questioning more radically the notion of subject leave us? Ricoeur (Eymar, 2005), for example, holds that the “I” cannot be reduced to being a mere subject of knowledge, but rather is a real being that cannot apprehend himself directly. His being-in-the-world is prior to the reflection and the establishment of an “I” confronted, as subject, with a world of objects. With what new category or concept do we recognize this “being-in-the-world”?

The problem is not solved, as we feel Wittgenstein attempts to do, by simply declaring that there is no cognoscente subject. Merely eliminating it does not solve the problem since it does not offer an alternative to the perception process that is compatible with the theory that knowledge comes about in association with language games. If there is no cognoscente subject, what is there? Can there be a speaking, participating, acting, playing subject if there is not a cognoscente one? Not answering this from the philosophical perspective that has brought down the epistemology has ended up passing the problem on to the social sciences.

Luhmann, whose interest is in the observation of society and not particularly individuals, takes for granted that all of the human dimensions from the organic and psychic systems converge in the individual, but that for the reproduction of communication itself, which is what constitutes sociological observation, the “black box” concept can be used with respect to the individual. This is because, for the study of communication, a knowledge of what is happening inside the individual is not necessary, nor is it necessary to know the “essence” of things (Luhmann, 1999: 121).

From my observation of sedimented semantics captured in a conception of culture as a semantic domain and a socio-cultural matrix, the communicative implications of accepting, even for theoretical reasons, the definition of the human being as a psychic system is unsettling, since that evokes the Kantian subject. Accepting the definition of human beings as systems of consciousness whose thought-based operations allow them to couple with communication systems since both, thoughts and communications, operate on the basis of meaning, once again places the emphasis on something like “the mind” and thoughts.

The concern for reductionism allows us to make a general criticism of sociology—or any other social science—inasmuch as, in a search for theoretical clarity, it simplifies the human being in order to focus on the social or language aspect, or whatever the “object of study” is. If we truly want to overcome reductionism, how can we observe concrete individuals in their complexity, not yet grouped into classes, strata, roles, or collective identities; that is, in their subjectivity? The specific problem we are faced with is, how can we observe subjectivity, which is, by definition, personal, nontransferable, unique? Is it possible to access, even on an abstract level, shared elements of subjectivities? In short, how can it be possible to address the problems suffered by individuals in contemporary society?

Our hypothesis is that, at the level of semantics sedimented in communication, it is possible to identify a gradient of these assumed semantics, moving from the unique specificity of the subjectivity of each concrete individual through the shared presuppositions at the level of interactional systems, groups, institutions, territorial contexts, and on up to the broadest level, that of modern Western society. As we move from more specific to more general contexts, the shared presuppositions become ever more abstract, retaining a coherent unit of meaning among them.

Culturally, it is possible to conceive of a continuum in which the individual is on one level of reality and has a constellation of unique presuppositions; the interactional systems are on another level with shared presuppositions, and so on, until global society is reached.

This perspective allows us to broaden the reductionist conception of the individual. In effect, from the cultural perspective as a reduction of the complexity of social communication that we have proposed, we find unique presuppositions at the subjectivity level, the level that would correspond strictly to the individual (the psychic system in the theory of social systems); but in a relationship of dialog (an interactional system), they cease to be individual and move on to another emergent communicational level, continuing thus until reaching the macro social level.

We can wonder, then, does the individual continue to be an “individual” inserted into the social situation, that is, in communication? The theory of social systems helps us to determine the fact that at the social level, the individual level (the psychic system) gives way to an emergent communication level, and it is that level that communicates rather than the individual. For the theory of social systems, communication constitutes an emergent system in which the individual (the psychic system) belongs to the environment. According to social systems theory, the psychic or awareness systems do not communicate; they only think, and it is through their thoughts that they couple with social communication.

The theory of social systems—which we could venture to say is prey to an (understandable) disciplinary reductionism—no longer asks about the individual. But it offers us the possibility of observing it in the social gradient of levels of presuppositions belonging to an emergent level which transcends it. However, if we adopt the viewpoint of the individual himself, he does not “remain” in the environment; he is still in some way (coupled with) communication in society, but no longer as an individual. As what? If he is not an individual, does he stop “being” (the quotation marks attempt to skirt the ontological issue, as it is an observation)? Or does he continue “being” in an expanded conception of individual to which “individual” semantics no longer apply, with all of their reductionistic burden that has been dragged along for nearly 400 years? How can we break away from these semantics, so deeply sedimented in our modern socio-cultural matrix? Don´t we need a new term for us humans? What shall we call ourselves then, if we do not want to end up in a new reductionism? We shall move from this point to Transdisciplinarity, in search for possible answers. Why TD? Because it offers the possibility of addressing the continuum in which to be an individual happens just in one level of Reality, while in others we humans cease to be individuals, but still “are”.

6.- Challenges for TD: legitimization in the scientific context

“We are but beginning the exploration of the different levels of Reality joined with the different levels of perceptions. This exploration marks the beginning of a new stage of our history based on the knowledge of the outer universe in harmony with the self-knowledge of the human being”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

In addressing TD, searching for propositions to overcome reductionism, I will focus on levels of reality and the constitution of the human being.

I have stated that the flow of social communications as the process that constitutes the evolution of society (Luhmann 1991, 2007) is sustained by what I have called a socio-cultural matrix, which, in turn, as a result of the same process of evolution, will eventually be replaced. As we have seen when discussing the crisis of modern epistemology, the notion of subject is in the process of losing its long-term centrality and there is room for new visions of the human being to become predominant.

From the cultural point of view I have proposed, the semantics of individuality, born out of the Cartesian-Kantian notion of subject, that has been solidly sedimented in our modern socio-cultural matrix, is on its way to being replaced by semantics more in accord with the evolution of society in these last three to four centuries. Now is when there is the possibility for a less reductionist conception of the human being to become adopted. It is society as the emergent level of communications that will in the end select new semantics that will undergo a sedimentation process to end up replacing the presuppositions in our modern socio-cultural matrix and thus start orienting social communications in a new direction. But it is up to us humans in the environment of society to irritate social systems with our new semantics, aiming for them to be selected and restabilized.

So will the new semantics that will sediment into a new presupposition about the human being come from a TD perspective? Will it come from a postmodern one? Or a neo-fundamentalist one? Evolution and our ability to get our ideas through the functional communicational systems have the final say. There are two major social systems that are crucial. The first one is science and, through it, education, and the second is mass communications. So here lie the two mayor challenges for TD: how to get its quite radical ideas not only to be accepted, but to be taken as the most promising perspective for meeting scientific complexity and responding to the social problems and challenges ahead.

Each of these functional systems has its own requirements and, therefore, puts forth different demands. I am not the one to analyze the status that TD has or should have in the scientific system, or what should be done for it to be fully legitimized and included. However, I will take the liberty to express some of the concerns that assail me.

Legitimization in the scientific context seems crucial for TD; this also implies legitimization within philosophy since TD is both an epistemological approach as well as an ontological one. It is not enough that it be proposed as an alternative to scientific reductionism, as there are already non-reductionist views of reality in philosophy and the sciences, as we have seen when speaking of the crisis in modern epistemology. The issue of legitimization within the scientific world is an insuperable prerequisite for it to exist in the world of education and of common sense, that is, in culture. This is because in modern society, it is the scientific system that has the privilege (the function) of distinguishing knowledge that is valid from that which is not.

TD itself recognizes this in its acknowledgement of the scientific disciplines. However, the scientific system has rigorous demands. This brings to mind Philip Clayton’s cautionary statements last year in his opening lecture when he wondered if TD would be “destined to be forever an amateur sport, with no shared standards, rigor or criteria for success? …Will the field ever win respect or exert a broader influence?” (Clayton,2007).

The challenge of legitimization within science is so great since it takes aim at the validation criteria itself of a scientific proposal. Can scientific criteria today accept, for example, the assertion that TD has its origins in the same scientific spirit which includes the rejection of all a priori answers and, at the same time, that it revalues the role of deeply rooted intuition, of imagination, of sensitivity, and of the body in the transmission of knowledge (Nicolescu, The transdisciplinary evolution of learning); or that TD entails both a new vision and a lived experience? Or that it is a way of self-transformation oriented towards knowledge of the self, the unity of knowledge, and the creation of a new art of living in society (Nicolescu,1996)?

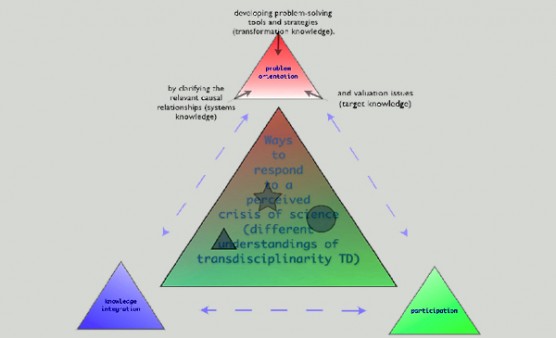

The very definition of TD can seem to be a puzzle in the face of the criteria of scientificity when one affirms at the same time that disciplinary research concerns, at most, one and the same level of Reality; on the contrary, Transdisciplinarity concerns the dynamics engendered by the action of several levels of Reality at once. While not a new discipline or a new superdiscipline, Transdisciplinarity is nourished by disciplinary research… Although we recognize the radically distinct character of Transdisciplinarity in relation to disciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, and interdisciplinarity, it would be extremely dangerous to absolutize this distinction… Transdisciplinarity is often confused with interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity…this confusion is very harmful to the extent that it functions to hide the different goals of these three new approaches (Nicolescu,1996). The confusion arises because not even those who are interested can accept the novelty of TD’s proposals in its entirety, much less those of strict scientific thought.

In effect, TD cannot be evaluated from the scientific criteria of today precisely because it is attempting to overcome them. And this implies not only transcending reductionism; it also implies a new conception of science. Just as the crisis of the modern episteme has implied a revolution within contemporary philosophy and the revolutionary authors propose simply to leave epistemology aside as the 17th century philosophers turned away from scholasticism, science seems to need a revolution as well. Perhaps this is what Nicolescu is aiming at when he affirms that science by itself could never respond to some basic questions because its own methodology limits the field of its questions and therefore a new Philosophy of Nature, attuned to the considerable attainments of modern science, is cruelly lacking (Nicolescu, 1991:39). Allow me here the audacity to propose that a task such as this, which calls on the leading contemporary scientists more than on TD interpreters from different scientific subspecialties and related fields, should take precedence over the dissemination of TD, given the risks that Philip Clayton pointed out to us last year.

Just as an example, I will mention the risk of falling into the migration of concepts from one field to another, against whose illegitimacy Professor Nicolescu warned us in his lecture at last year’s conference. This appears crucial when dealing with levels of reality. The author clearly differentiates what he defines as levels of Reality from, for example, levels of emergency in systemic theories.

In Niklas Luhmann’s sociological theory, levels of emergency are defined as follows: “…emergent orders are spoken of in this context; this refers to the irruption of phenomena that cannot be derived from the properties of their components” (Luhmann 2007:100). Indeed, psychic systems give rise to communicational systems whose properties cannot be reduced to the systems of consciousness from which they emerge. But this does not authorize us to speak of different levels of Reality as TD understands them.

Let us hear what Professor Nicolescu says about reality and levels. He defines reality from the perspective of a physicist in his daily work: the physicist encounters “something” which resists theories and experiments, and it is this resistance that gives the “something” the attribute of “reality” (Nicolescu,1991:97). This way, the “reality” of which he is speaking is not simply a creation of the human mind, but “neither is it something in itself, for we intervene…with our interpretation” (op.cit.:97). There is no room here to discuss the differences and similarities between this “realistic” conception of reality and the more “constructivistic” one sustained by the social systems theory. What concerns us here is the fact that TD has a very specific conceptualization of levels of reality, as well as the fact that it is not rigorous to use these in another context or in metaphoric language. The same is valid for the concept of level.

Nicolescu defines levels of reality as a group of systems which remain unchanged under the action of certain transformations. For a truly different level of reality to be seen, he states, there must be a breakdown of language, of logic and of fundamental concepts. This applies to the quantum level and the macroscopic level in physics. This rigorously defined concept shall not be illegitimately “exported” to levels, dimensions, domains, or orders used in other theoretical contexts, nor shall it be talked about loosely.

If this occurs, the central concepts of TD will be undermined and the possibility of their influencing the scientific system will be diminished. If we who share the TD perspective do so, we are digging our own grave.

7.- Challenges for TD: culture and a new notion of the human being

“L’homo sui trascendentalis is being born. He is not any ‘new man,’ but a man that is being reborn. This new birth is a potentiality etched on our very being”

(Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity)

I will now address the challenges TD faces in offering a better, non-reductionistic notion of the human being that can eventually replace the sedimented semantics of “individual” that is still at the heart of our socio-cultural matrix. I will do this from the cultural point of view I have proposed. From there, I shall ask TD if the concepts it is using to express what it means to be a human being really overcome the semantics of individuality born out of the Cartesian-Kantian notion of subject that has been solidly sedimented into our modern socio-cultural matrix.

We have said that TD offers the possibility of addressing the continuum in which being an individual happens in just one level of Reality, while in others we humans cease to be individuals, but still “are.” If we humans are individuals only in one level of our “being”, what shall we call ourselves then? Isn’t it as if we were to address our entire body and call it hands? Or stomach? I believe that, just as there is a cruelly needed philosophy of Nature, indeed a scientific revolution, there is also a desperate need for a new, non-reductionistic term to call ourselves as human beings.

Let us look first at the conception TD has of the human being. A first affirmation is that our bodies have both a macrophysical and a quantum structure (Nicolescu,1996:9). From the material, physical point of view, it is clear that we human beings are made up of at least two levels of reality, the two levels of reality recognized by science based on the discoveries of quantum physics. But TD goes further and asserts that “The different levels of Reality are accessible to human knowledge thanks to the existence of different levels of perception, which are in biunivocal correspondence with the levels of Reality… To the flows of information that pass coherently through the different levels of Reality, there corresponds a flow of consciousness that passes coherently through the different levels of perception (Nicolescu,1996:23). Physics has undoubtedly already made the acceptance of different levels of reality irreversible, but is there scientific proof that for each one there is a corresponding level of human perception? Isn’t it thanks to sophisticated instruments that physicists have been able to access the subatomic level of reality? What level of perception corresponds biunivocally to the subatomic level of reality? Additionally, what evidence has been presented in the proposal of Husserl or his followers of “the existence of different levels of perception of Reality on the part of the subject-observer?” (op.cit:10) We have here a theoretical tangle that constitutes a challenge worthy of being further developed by TD as it dialogues with sciences that study perception and related processes.

But TD penetrates territories that are still a mystery to the sciences and touch what is “sacred.” It asserts that “the set of Reality levels stretches through a zone of non-resistance to our experiences, representations, descriptions, images, or mathematic formulations. And this “non-resistance zone corresponds to what is sacred” (Nicolescu, 1996:22). What is the human being’s relationship with this zone of the sacred? TD holds that, just as the coherence among levels of reality presupposes its non-resistance zone, what constitutes the “transdisciplinary object,” isomorphically the coherence of levels of perception, presupposes a zone of non-resistance to perception. Thus, the set of levels of perception and its non-resistance zone constitute the “transdisciplinary subject.” To TD, then, we human beings are transdisciplinary subjects who have a flow of consciousness in an isomorphic relationship with the flow of information that moves through the levels of Reality; the two flows are associated thanks to the same non-resistance zone, that is, that which is sacred. The transdisciplinary subject, then, would be the set of levels of perception and their zone of non-resistance through which consciousness flows, a flow that unites with the information of the levels of Reality, producing an (open) unity between subject and object thanks to the non-resistance zone which acts as an included third, that which is sacred.

Expressed thusly, we human beings, who until today have described ourselves as individuals, where do we start and where do we end? Do we have, or are we, the levels of perception? Do we have a consciousness, or are we the flow of consciousness? Are we in the non-resistance zone, are we part of it, or are we the zone itself? Do we have access to what is sacred, or are we sacred? In each being there is a sacred, intangible core, asserts TD (Nicolescu, The transdisciplinary evolution of learning).

This beautiful description of our human constitution has the monumental task of making its way into the scientific system, which would require nothing less than the revolution in scientific thought of which we have already spoken. But even more important is that it make its way into our culture, that is, into the social communications that struggle to become legitimate, be selected, and one day become the semantics sedimented into the socio-cultural matrix. How do we move away from a conception of ourselves, inherited from the Kantian subject, that makes us perceive ourselves as individuals, isolated, material, superior beings and masters of Nature, living in a single level of reality, subjects confronted with a world of inert objects placed there for our exploitation or our sensorial pleasure?

We create a new term (we leave concepts to science), a term so new and so strong that it can set aside the old ideas about ourselves. A term not for describing, but rather for evoking, all that we are, including the sacred. A new term, free from religious connotations even though it will express what all religions have been saying for millennia. Is TD using its best expression when speaking of “transdisciplinary human beings”? Was the poet using his best expression when he created the term transdisciplinary attitude? (Roberto Juarroz, in Nicolescu 1996:36). The concept is beautiful; I could even add that there is no way to understand TD unless we are in a transdisciplinary attitude. But this open, loving attitude, which is innate to us humans, just as in each of us there is a sacred core; what does it have to do with disciplines? Of course it was a gift from the poet to a promising new way of looking at the world, but, when it comes to naming ourselves, overcoming the reductionistic expression of “individual” we want to do away with, shall we call ourselves transdisciplinary human beings? Isn’t it a bit… long?

It would be less appropriate and even dangerous to use transdisciplinary “subject.” From a conception of culture as a semantic domain and a socio-cultural matrix, the communicative implications of utilizing the term “subject,” inasmuch as it evokes the Kantian subject, make the expression “transdisciplinary subject” a poor choice. Of course, in a scientific context the concept is probably less at risk than in a cultural one, and it could continue to be used in dialogue with disciplines to which it would cause no problems. But in the context of the philosophical revolution that overcame epistemology, in most of the social sciences and especially in social communications, including the educational system, there is a need for a renovated term for us human beings.

These are some of the challenges TD faces in overcoming the reductionistic notion of the human being. From the cultural point of view I have proposed, there is no doubt that evolution will eventually replace the sedimented semantics of “individual” that is still at the heart of our socio-cultural matrix. We human beings are much too uneasy with the social problems that the semantics of the “individual,” with all of its reductionist burden that it has dragged along for almost 400 years, is inflicting on the final stages of our Modernity.

Responding to these challenges is what has seemed to me to be the long way from non-reductionism to Transdisciplinarity. TD is our final goal, but it will not be an easy road to take. It can be traversed only with a TD attitude, optimistic, at once guileless and obstinate, unwavering yet flexible in order to adapt our discourse and our strategies to the demands imposed by today’s social complexity. How could it be otherwise if TD, as we can read it in the Manifesto, “is a generalized transgression that opens an unlimited space of freedom, of knowledge, of tolerance, and of love”?

References

Beck, Ulrich, 1998. ¿Qué es la globalización? Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós

Clayton, Philip, 2007.”Disciplining the Transdisciplinarity: the religion-science revolution and five minds for the future”.Metanexus Conference, Philadelphia

Dockendorff, Cecilia, 2006. “Lineamientos para una teoría sistémica de la cultura: la unidad semántica de la diferencia estructural”. En Francisco Osorio y Eduardo Aguado, eds. La nueva teoría social en Hispanoamérica: introducción a la teoría de sistemas constructivista. Toluca, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

Dockendorff, Cecilia, 2007. “Teoría Sociológica, Cultura Moderna y Emancipación: un ejercicio inconcluso de auto-aclaración sociológica.” Santiago de Chile, Revista MAD, Magíster en Antropología y Desarrollo, Universidad de Chile.

Eymar, Carlos, 2005. “En memoria de Paul Ricoeur”. En El Cicerone, Revista El Ciervo. Barcelona.

Foucault, Michel, 1993. Las palabras y las cosas. Una arqueología de las ciencias humanas. México, Siglo XXI.

Giddens, Anthony, 1995. Modernidad e Identidad del Yo. Barcelona: Editorial Península.

Habermas, Jürgen, 1992. Teoría de la Acción Comunicativa. Madrid, Taurus Ediciones.

Hall, S., Held, D., and McGrew, T. 1992. Modernity and its Futures. Cambridge: The Open University and Polity Press.

Larraín, Jorge, 2005. ¿América Latina Moderna? Globalización e Identidad. Santiago: LOM

Luhmann, Niklas, 1991. Sistemas Sociales, lineamientos para una teoría general. México D.F., Alianza Editorial.

Luhmann, Niklas, 1999. Teoría de los Sistemas Sociales II (artículos). México, D. F.: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Luhmann, Niklas, 2007. Sociedad de la Sociedad. México, D. F.: Herder, Universidad Iberoamericana.

Maturana, Humberto,1990. Biología de la cognición y epistemología. Temuco, Ediciones Universidad de la Frontera.

Nicolescu, Basarab, 1996. La Transdisciplinariedad. Manifesto. Traducción al español, revisada con el autor, de Norma Núñez-Dentin y Gérard Dentin.

Nicolescu, Basarab, 1991. Science, Meaning and Evolution – The Cosmology of Jacob Boehme, with selected texts by Jacob Boehme, Parabola Books, New York.

Nicolescu, Basarab …The transdisciplinary evolution of learning

Rorty, Richard, 1995. La filosofía y el espejo de la naturaleza. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra.

Wallerstein, Immanuel, 1996. “La Reestructuración Capitalista y el Sistema-Mundo”, en Raquel Sosa. Perspectivas de Reconstrucción. ALAS-UNAM, México.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, 2004. Investigaciones filosóficas. Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Barcelona: Editorial Crítica.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, 1988. Sobre la Certeza. Compilado por G. E. M. Anscombre y G. H. von Wright. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa.